Reaffirming Engagement

Breathing life back into our streets post-covid-19

The health of our cities - measured by their ability to provide safe, equitable and vibrant futures for their inhabitants - will determine the quality of life for many of us as we continue to become a majority urban species.

Keywords: public space, collective agency, advertising, subvertising

Jordan Seiler installs one of his artworks in Oslo, 2019

Cities are, quite frankly, our only option if we choose to continue our explosive population growth while balancing our impact on the planet; treading the fine line between sustaining our global ecosystem or overburdening it with our desire. The efficiencies they provide cannot be overstated, and our embrace of their concentrated verticality must be inevitable. Luckily for us, they also happen to be where most of us want to live.

As unremarkable as this may be, our continued affirmation of this fact is an important acknowledgement because it renews and re-focuses our attention on the creative process of building the place in which we live. Often, cities can feel as if they sprang from the ground wholly formed, fixed in place by someone else long ago. But we must continually remind ourselves that cities look, smell, sound, feel, and work the way they do not because of some preordained set of rules, but because of the decisions that we make today in an effort to shape them for tomorrow.

Empathy Machine: cities as conduits to equity

When speaking about cities, Morag Rose, a Manchester-based psychogeographer says that “the streets are a place of encounter, diversity and mundane forms of magic” the two former creating the latter. By distilling the function of city streets down to this fundamental idea, we can more easily see how cities create the conditions for positive coexistence. Through diverse encounters and the opportunity to encounter diversity, cities unleash a certain alchemy, a mundane magic that conjures empathy out of thin air.

Empathy is the first and most important step in the pursuit of equity. It is the foundation upon which we build a mental picture of the world that includes others needs in addition to our own. Those who can encounter diversity and still resist the pull of empathy are few and far between. For this reason we find cities to be bastions of those liberal ideals which encourage inclusion, respect, and a vision of the future in which we share the bounties of our collective creativity.

NYC, circa 1982

A panoply of voices: diversity in the city

I was born in New York City in 1979 and have continued to live there for the past 40 years. I am a native New Yorker, and over the years my bond with the city has only grown. The older I get, the more I come to realize that I am a direct product of this great metropolis. The more deeply I understand this fact, the more I care about how the city functions, and in turn how the city influences the person that I am.

This is a feedback loop that reinforces itself over time, growing stronger with each passing day, and I am not the only one for whom it is true. New York is filled with citizen advocates that will enthusiastically tell you what they love about this city, only to passionately follow those items with the long list of things that must change.

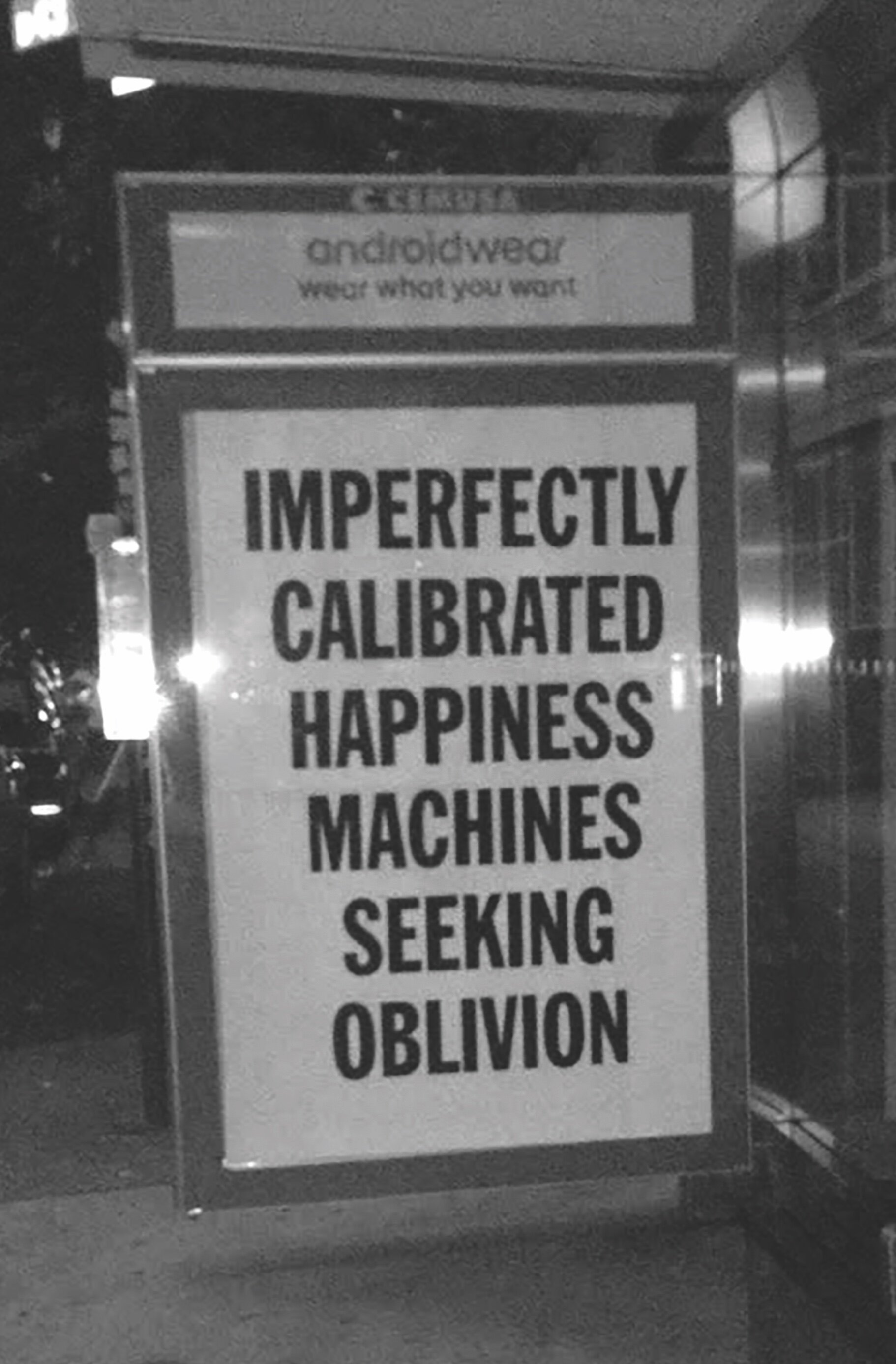

Many years ago, unable to articulate my grievances with New York City, I began to fight the tyranny of advertising in our shared public spaces. Advertising was ubiquitous, overwhelming, simple and routine - the opposite of what I knew my city to be. Stepping out onto the street, I found myself on a collision course with a panoply of voices echoing against the concrete and steel.

It was invigorating to be centered amidst so much difference. And yet the walls of my city said the same thing, over, and over, and over again through the vehicle of advertising. The dull monotonous drum of capitalism reminding me of a singular imperative, to consume. Without language for my dissent, I put my hands to work.

Stavanger, 2016

At first I took to the streets with my own imagery, burying advertisements under my personal thoughts and ideas, and while I could not compete with the scale of outdoor advertising, I was able to exert a meaningful force upon the city. Questions were asked, articles were written and a conversation grew that while small in its scope, began to find an audience. As that audience grew, so did the criticism, mostly from those within the outdoor advertising world. It went something like this: What makes your thoughts and ideas any better than the advertisements that are already there? The answer was not forthcoming.

I had after all, replaced the monotonous tone of capitalism, with the monotonous tone of a cis white male. If I had the means, the ubiquity of commercial media would have given way to the ubiquity of my own inner consciousness. This was the beginning of a revelation that should have been obvious at the time, but instead unfolded slowly.

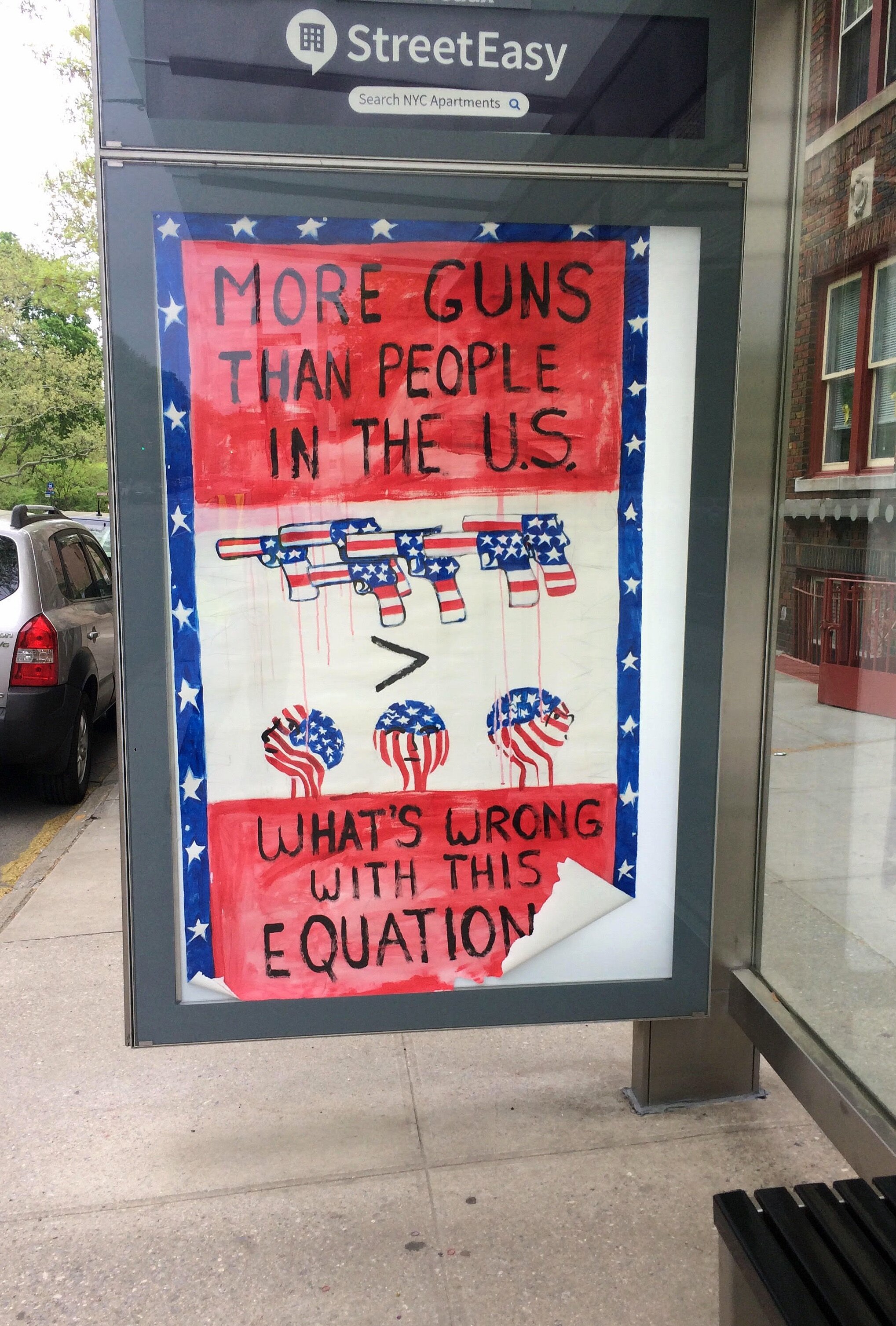

What I was learning was that if the monotony of advertising had to go, its replacement must be inclusive and reflect the city on which it had once exerted its power. Commercial media had to give way to a democratic civic media. The result was a project that I called PublicAccess, and an attempt to democratize who has access to the walls of our cities and the messaging systems we have built into our shared public spaces.

PublicAccess Keys

The idea behind PublicAccess is simple. Make the keys that outdoor advertisers use to lock away their messages in bus shelters, lollipops, and other standardized public advertising infrastructures. Then make those keys available to anyone who wants them. The result, while still plagued by issues of equity, is an attempt to remedy the monopolistic grip advertising had on the walls of our cities.

If before we encountered a homogenic monolith of thought, with PublicAccess and the democratic access it demanded, we might find diversity in not only the people of our city, but the ideas expressed on its walls. For me it was a revelation, and despite taking several more years before I came upon Morag's insightful words, a real-life example of how encounters with diversity formed one pillar of what I was striving to create in the hope of pushing my city towards a better version of itself.

Over the years this idea of encountering diversity has helped to guide my work because it is part of the magic that I believe makes cities so effective at creating safe, equitable and vibrant futures for their inhabitants. By increasing opportunities for both encounter and diversity, we provide a fertile mixture in which empathy is conjured without much fanfare. Most of us don't give it a lot of thought, but as Morag points out, it is one of the two ingredients that create the mundane magic that make cities an opportunity like no other.

Given space and time, this mundane magic is transformative, leaving behind a better world in the form of a more empathetic one. Provided that we cultivate and encourage it, I had come to believe that little was capable of standing in its way. That was until I found myself at home, several months into a global pandemic that has altered the conditions under which this mundane magic can be summoned.

A city without encounter, isn’t a city

In March of 2020, NYC was at a tipping point. Over 1000 people were dying every day from a communicable disease that was making its way around the globe on a vast network of international travel. We quickly shut our gates. Highly contagious, this pandemic was ripping through our local community at an alarming rate.

Knowing little about its transmission, our only recourse seemed to be to hide, and our local governments quickly mandated stay at home orders, business closures, and a near total shutdown of New York. My partner was at this point four months pregnant with our daughter. We took the orders seriously, as did much of the rest of the city. We only went outside for the essentials, groceries, doctors, and an occasional short walk for exercise and mental health.

These drastic measures worked, in part because they were so strictly adhered to. Days of isolation turned into weeks, which beat back the virus and brought down the death rate. It was a heroic effort that required the coordination of millions of people working together towards a singular goal.

I was proud of my city and the compassion we brought to bear on the task of creating safety for all. It was clear that New York was alive, a healthy city capable of profound acts of empathy and self preservation, ready to take on challenges of immeasurable scale. I was humbled, and felt a level of personal pride that reminded me how closely my own sense of being was intertwined with my city and its successes.

Over time, science came to understand the virus' behavior better and developed guidelines by which we could begin to reoccupy our streets. Masks, distance, and hygiene would be a bulwark against the pandemic that would allow us to intelligently repopulate our shared public spaces.

I anxiously waited for our slow return, but it didn’t happen. Instead, a self-imposed isolation emerged that troubled me deeply, and as the months passed, I began to find my city harder and harder to recognize.

Individually, we had made the difficult decision to limit our encounters, and the effects were profound. New York City was becoming a ghost, an unrecognizable phantom that wasn't quite dead, but neither was it alive. Ironically, it reminded me of the virus that had rushed in and caused so much harm: a benign body lying in wait for the right conditions that would give it life again.

Pandemic installation, 2020

Several months into the pandemic I began to take longer walks, searching for the city that I once knew, and witnessing what it had become. What I found was an affirmation of the second pillar behind Morag's insightful words and a guiding principle behind my artistic practice since the PublicAccess project began: a city fulfills its promise by conjuring empathy through encounter and diversity. It cannot succeed without both.

What I discovered on the empty streets was evidence that a city, like a virus, can have all of the necessary components for life and yet still be dead. The machinery intact, a diverse measure of people, buildings, and institutions: but without those components under the influence of encounter, it would remain dormant.

The pandemic - in a swift and decisive gesture - had pushed us to sacrifice a vital component of our cities health, and with it the frictions that had warmed its internal temperature and conjured life from flesh and steel.

Re-engaging our cities

It has been almost a full year since those late night walks began, and New York has lifted many of the drastic measures it put in place to curb the pandemic. A slow vaccine rollout has brightened our horizons and given the city hope, yet today the streets are still largely empty. Those that have been reoccupied have generally been reduced to thoroughfares - highways conveying people hidden behind masks, six feet apart, doing their best to keep a distance that ensures our physical and social isolation.

Despite having the knowledge and tools to control the virus's spread, we have not returned safely to our streets, but rather remain isolated by fear, confusion and an abundance of caution. It’s completely understandable, and yet profoundly disheartening to watch as the pulse of New York slows, the magic on our streets waning, while we contemplate the conditions under which we might return.

This cannot stand. With the pandemic ragging on, the months giving way to a year, and that year giving way to yet another, we must remind ourselves to cultivate those increased levels of diversity and encounter so vital to our cities health. And so I propose that despite our fears, now is a time for action.

Talk To Me project

There is no recipe to create an encounter in your city, they should take on many forms and their diversity is our strength. You might alter how your city looks by changing out the ads like I do, or transform the way your city sounds by unleashing your own sonic landscape upon the streets. You could challenge how it feels to be in public space by offering comfort to those without, or manipulate how your city smells, and with that small deviation awaken our senses.

The challenge is to question how our cities work, carving out new desire lines and invigorating our streets by altering the built environment in subtle ways that replenish those moments of encounter we have lost. The diversity of tactics we use will only contribute to our final goal of conjuring the mundane magic so vital to our cities.

My work, fighting the monotony of advertising and cultivating diversity on our walls, was intended to make an already vibrant and healthy city better. Today the task before us is far more fundamental. We must, in spite of the conditions of our isolation, reinvest time and energy in our shared public spaces, the streets, and the health of our cities.

This is no small feat. We are still deep inside a global pandemic that threatens not just the health of our cities, but the very bodies that occupy them. Yet if we fail to recognize the problems ahead, we risk losing what brings our cities to life; to encounter with friction, again and again, the diversity of our fellow citizens.

And so I leave you with this. If you believe like I do, that cities thrive on encounter and diversity, then now is not the time to hold ourselves back. Now is the time to reconfirm our commitment to the streets by re-engaging our cities so that they can once again fulfill their promise to create the mundane magic, that conjures the empathy, which summons the more just, equitable, and vibrant futures that we all deserve.